For optimal reading, please switch to desktop mode.

Federated cloud deployments encompass an ever-evolving set of requirements, particularly within areas of industry, commerce and research supporting high-performance (HPC) and high-throughput (HTC) scientific workloads. It's an area in which OpenStack really shines, through excellent support for federation protocols and its standard API for the manipulation of infrastructure primitives, but at the same time the reality is that no two deployments are entirely alike - and this can cause problems for both users and operators.

If you're an optimistic sort then you could in fact view this as a strength of the platform, as it means that a given installation can be tailored according to the workload. For example, you might have one installation at a particular institution that's designed for provisioning and presenting interfaces to databases, and another which is developed to run a HPC job scheduler such as SLURM. Practically speaking though, the fact that each is installed on completely different selections of hardware, each according to the workload, is of no interest to our users. What they do care about is having access to each in a way that isn't bogged down with too much bureaucracy or burdensome tooling.

To that end, one of the key themes that overarches almost any architectural discussion with regards to federated cloud workloads is that of authentication and authorisation infrastructure (AAI). The need to provide a secure and compliant solution, yet one which is (ostensibly) seamless and as pain-free for users, is certainly a challenge - and getting this right is fundamental to a platform's adoption and its success.

Fortunately there are myriad tools and technologies available to help meet this. Keycloak is one such application, and it's one that we at StackHPC have been experimenting with as a proof-of-concept in order to provide the AAI 'glue' between two cloud deployments that we help to operate.

A few people have asked us to share our experiences and so this blog post is an attempt at summarising those. Also note that this post focuses on browser-driven interactions, as you'll see that a lot of the redirections make use of WebSSO where a web browser is required. A future blog post will delve into interactions using the API via OpenStack and related CLI tools.

Introducing Keycloak

First and foremost, Keycloak is an identity and access management service, capable of brokering authentication on behalf of clients using standard protocols such as OpenID Connect (OIDC) and OASIS SAML. It's the upstream version of RedHat's enterprise Single Sign-On offering and as such is well supported, developed and maintained.

Keystone already has good support for federated authentication in a variety of contexts, and there are existing services such as EGI's Check-in and Jisc's Assent that provide identity brokering using compatible protocols, so why introduce another moving component into the mix?

There are a number of reasons:

- You might want to be able to associate identity from a number of different sources for a particular user's account;

- You might want to standardise the authentication protocol for Keystone on OpenID Connect but offer support for integration with identity providers using SAML;

- A hub-and-spoke architecture (as outlined in the AARC Blueprint) might be preferrable to tightly coupling individual OpenStack clouds with one another in a full-mesh configuration, which is the case when using Keystone-to-Keystone;

- You might need to be able to federate user authentication via internal sources (such as an Active Directory instance);

- ... and so on.

For us, it was about being able to add another layer of control and flexibility into the authorisation piece. A proof-of-concept federated OpenStack using two disparate deployments was integrated using the aforementioned EGI Check-in solution, and while this worked well we often found ourselves wanting more control over the attributes, or claims, that are presented and subsequently mapped via Keystone as part of the authorisation stage.

Identity brokering with Keycloak

Authentication

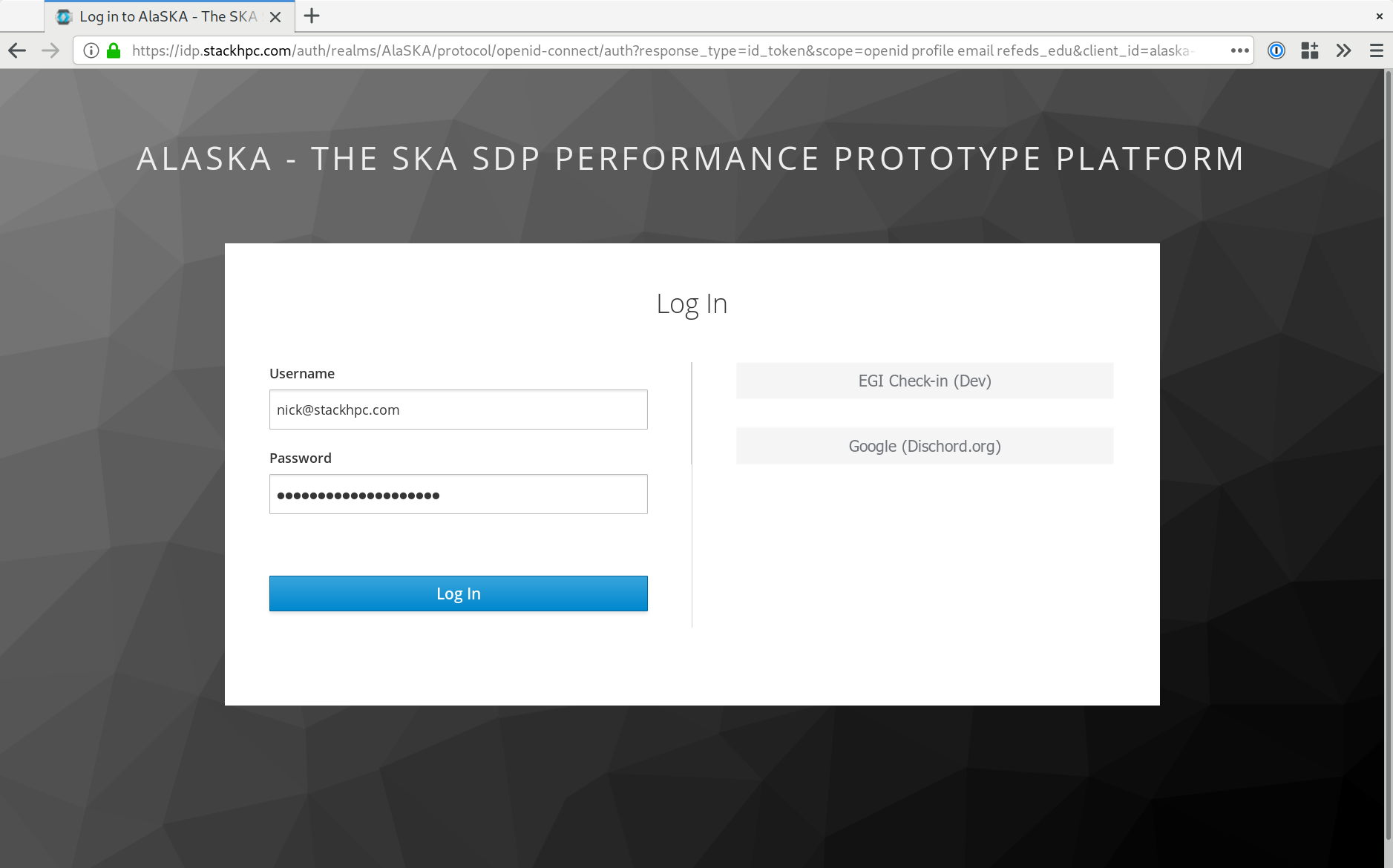

Let's review how Keycloak fits into the equation. A user makes a resource request via their service provider, which in return expects them to be authenticated. When Keystone is configured to use an identity provider (IdP), the user is redirected to the IdP's landing page - which in our case is Keycloak. Here the user is presented with a selection of login choices. Depending on their selection, they're then redirected a second time in order to perform the authentication step, and then Keycloak handles the transparent redirection and security assertion back to Keystone. At this point access is granted, assuming the right mappings are in place to grant membership of the user to a group which has permissions within scope of a project. On paper this sounds somewhat convoluted, but in practice it's reasonably slick and intuitive from a user's point of view:

In my case (in the video above), the Horizon login page redirected me to a Keycloak instance, which presented me with three authentication options. I selected the option which deferred this to EGI's Check-in service, in which I again deferred to Google, and I then used my StackHPC credentials. This provided Check-in with some context, which in turn was passed back to Keycloak, and onwards to Keystone. As part of this final step, Keystone is configured to map a particular OIDC claim containing my company affiliation to a stackhpc group which has the member role assigned in a stackhpc project, thus granting me access to resources on this service provider.

This little demonstration neatly shows one of the immediate benefits of introducing Keycloak into your federation infrastructure - being able to maintain control over a diverse selection of potential authentication sources. At this point, I have an identity within Keycloak that an administrator can associate with other AAI primitives, including multiple IdPs, groups, security policies, and so on.

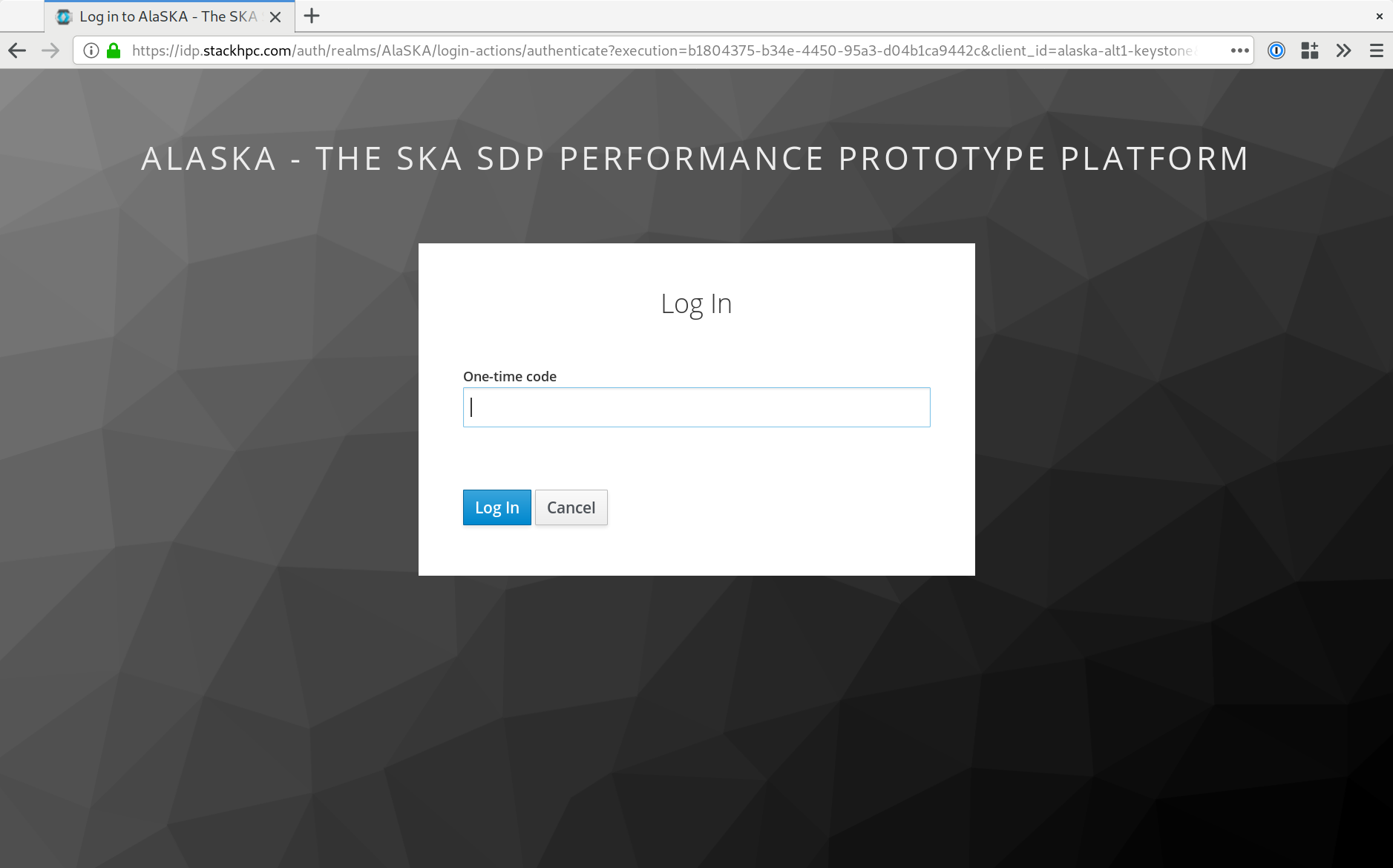

Integrating OTP

A little side note on what else is possible with Keycloak, a feature that could be of use even if you aren't interested in delegating authentication to another service. Keycloak provides support for One Time Passwords (OTP) - either time-based or counter-based - via FreeOTP or Google Authenticator. Thus, it's possible to federate your users with something such as Active Directory and at the same time add in another layer of security in the form of two-factor authentication.

Once a user has first signed up to Keycloak, either directly (such as via an invitation link), or indirectly by delegation to another configured IdP, the user can login to Keycloak and associate their login with an authenticator. With that in place, they can then access cloud resources on a given service provider using the credentials for their Keycloak account:

And then when prompted, enter the code generated using the Google Authenticator application:

If that's successful then then they're redirected back to Horizon with access to OpenStack resources - secured via two factors used during the authentication process.

Authorisation

As mentioned earlier, one of the problems we were trying to solve was normalising or having control over the identity-related attributes (claims) that are presented to Keystone. It's these claims that give the cloud administrator control over who gets granted access to what, and services such as Check-in make use of proving the entitlement context by hooking into external attribute sources such as COmanage or Perun. However, Keycloak can also assume the role of these components and populate claims based on its knowledge of a particular user. Let's take a quick look into this mapping process and then what the Keycloak configuration looks like in order to influence this process.

Here's a snippet of the JSON mappings file that's configured in Keystone and consulted whenever authentication is triggered via this IdP (Keycloak):

[

{

"local": [

{

"group": {

"id": "44a46f4e41504e01ae77008c88dfc2da"

},

"user": {

"name": "{0}"

}

}

],

"remote": [

{

"type": "OIDC-preferred_username"

},

{

"type": "HTTP_OIDC_ISS",

"any_one_of": [

"https://aai-dev.egi.eu/oidc/"

],

},

{

"type": "OIDC-edu_person_scoped_affiliations",

"any_one_of": [

"^.*@StackHPC$"

],

"regex": true

}

]

}

]

This basically tells Keystone to create and associate a federated user with the group that has the ID 44a46.. and a username of whatever OIDC-preferred_username contains, as long as these two conditions are met:

- The

HTTP_OIDC_ISSattribute ishttps://aai-dev.egi.eu/oidc/; - The

edu_person_scoped_affiliationsclaim matches the regular expression^.*@StackHPC$.

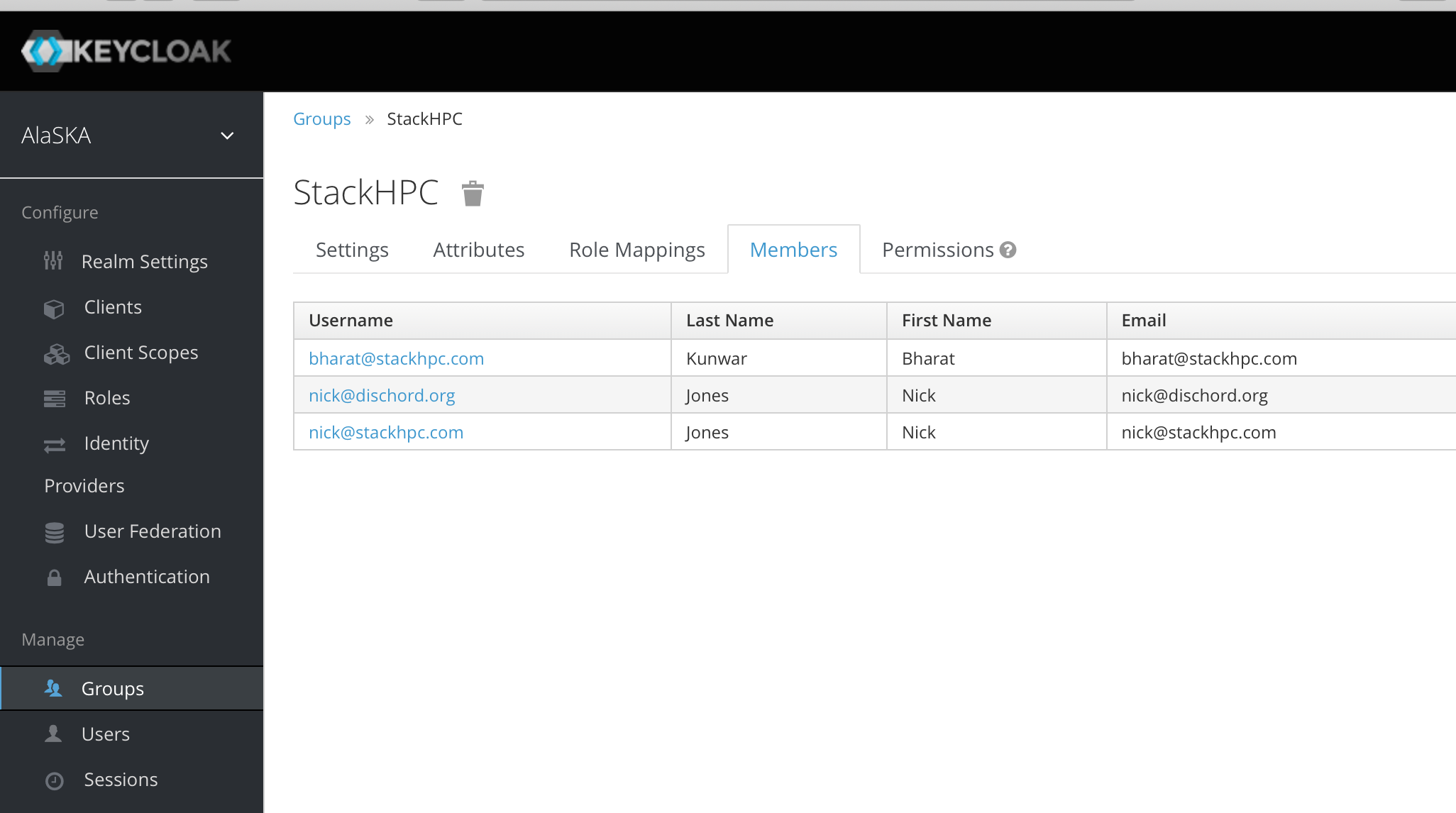

These are standard claims returned from EGI Check-in, however what if we wanted to make use of our own arbitrary grouping so that we're not just relying on the above selection in order to associate users with particular group? Keycloak lets you create your own group and user associations, and these are then (by default) in scope for claims presented to Keystone for mapping consideration. So we can expand the above example, and perhaps replace the OIDC-edu_person_scoped_affiliations section with something that makes use of what we get via Keycloak:

{

"type": "OIDC-group",

"any_one_of": [

"StackHPC"

],

}

Now, any user in Keycloak associated with the 'StackHPC' group, regardless of their authentication source (so long as it's valid!) will be able to access resources with whatever role is associated with the OpenStack group ID shown in the previous example. Here's what it looks like from Keycloak's point of view, in this group I have three users, each of which has different linked IdP:

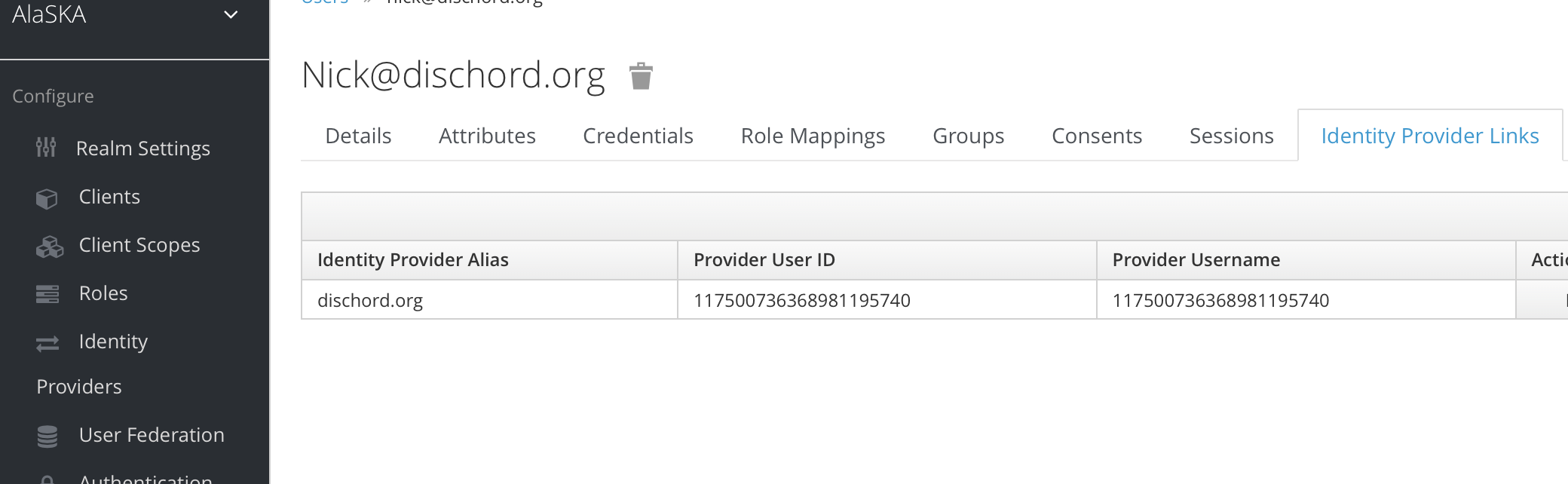

If we look at the linked IdP for my personal Google account:

The grouping is an abstraction handled by Keycloak, but it gives us control over which users have access to our OpenStack deployment. This is a simple example and it's possible to do much, much more - including specifying additional attributes to provide further authorisation context, as well as more complicated abstractions such as nested groups - but hopefully this gives you a flavour of what's possible.

Further information

Our proof-of-concept and investigation with federated Keystone would have been immeasurably more difficult if it wasn't for Colleen Murphy's fantastic blog posts, here and here.

It's also worth mentioning that the Keystone team are currently working on developing identity provider proxying functionality, which might make the requirement for Keycloak redundant in a lot of cases. The Etherpad used at the Berlin Summit for the Stein release to gather requirements is here, and there's some more information from the Stein's PTG Etherpad here.

Finally, we'd also like to thank our friends and colleagues at the University of Cambridge for their assistance with the infrastructure resources that made this proof-of-concept possible.